The author / photographer in 1973 on Thompson and Spring Streets in SoHo. One of the World Trade Towers in background,

I have always had an interest in history: in how past footprints impact the present. It was the urbanscape that led me to New York City in the early 70's. The streets, the architecture, the piers, the parks, the waterfront of an old American city. The city was losing its population and its businesses and had a reputation for being dangerous and dirty. But my generation of ‘downtown’ New Yorkers embraced the city's image and found the rundown tenements, empty warehouses and neglected townhouses desirable and cheap. Many of us were artists who identified with past bohemians and the old streets before us. The city was like a movie set where we felt like we could write the script. We also related to the remnants of past immigrants - Italian, Irish, Jewish, Chinese, and the slew of recent ones - Puerto Ricans, East Europeans and more Chinese. Their restaurants and bodegas drew us in. We were the new curious set of immigrants in downtown New York and we gave the city a renewed value, thus making it more desirable for the next and current generation. This recent history I know well, since I lived and created in its midst. Today this wealthy island is experiencing a 21st century boom and many of the city’s footprints are disappearing. This current change has only increased my interest in an earlier history of Manhattan.

When I first came here I did what all New Yorkers do, I walked. It was easy to navigate the infamous New York grid with the parallel number streets and avenues, but downtown was different. This was the old New York whose streets were laid out by several earlier farm grids from 200 years of colonial life. A few alternations were also made in the early 20th century with the advent of the subways and automobile. I never used a map in my early walks. It was always fun to get lost and be surprised wherever you ended up. In recent years, since becoming a tour guide, I started to carry some of the earlier maps before the grid, the ones before 1811Commission Plan.

When the Dutch East India Company established a fur trading post at the southern tip of the island, there were already footprints. The Lenape, the original inhabitants, called the island Manahatta, “the island of many hills”, and had their foot trails and seasonal settlements and their points of entry and departure. They navigated around the many hills and outcrops, as well as the various streams, ponds, tidal marshes and freshwater bogs. The Dutch soon built a fort, established a city and laid out several large farms (boweries) off the main Indian path, the Wickquasgeck Trail, that ran the length of the island. Parts of this beginning stretch was already cleared by the native people for agriculture. The path was widened for wagons and called Bowery Lane which became the present day Bowery. No 1 Bowery, a land tract, was given to the Dutch director-general of the island. It contained much of what is now the East Village. The last director–general, the legendary Peter Stuyvesant, eventually bought the land and remained there when the English took over the island in 1674. 100 years later, when the English evacuated the city on Nov 23 1783 after losing the American Revolution, his descendants were still living there.

During the Revolution, the city's population fluctuated from 25 to 15 thousand and back. By the time of the first census in 1790 - after being the capital of the new United States for five years - New York City was up to 33 thousand inhabitants. The city would continue throughout the 19th century to lead the new nation in finance and commerce with a population explosion to match.

The city would reach 100 thousand by the time of the Commission Plan of 1811, which laid out the infamous New York grid, a dozen or so parallel avenues crossing 155 parallel streets at right angles. Today the parallel streets go to 220th Street.

This Manhattan real estate plan was drawn up by a young surveyor, John Randal, working with a three man commission and with older city plans and maps. Working another decade, he created 92 farms maps of early Manhattan, of what was in the way for implementing this rectilinear grid of streets. These maps show in great detail where houses, buildings, farms, property lines and the colonial roads were along with the remaining natural topography - springs, streams, ponds, marshes and various elevations.

It would be nearly 75 years before all the streets were laid out to 155th. By mid century ( 1853) when the city began planning Central Park, which was not on the Plan, there were close to a half a million people on Manhattan. When Central Park’s initial phase was finished by 1872, the island had reached one million. Manhattan peaked at 2.3 million in 1910. “High rises" had hardly started. 50 floors were tops and they were all office buildings. Today 100 years later the city population is down to 1.7 million. (More on NYC population growth and shrinkage in future blogs.)

The 1811 plan made the east and west streets 60 ft wide. Approximately every tenth street and the north and south avenues are 100 ft wide. Each block was relatively uniform: 200 ft wide (uptown) and 800 ft long (crosstown), though the blocks in the middle - 4th (Park Ave), 5th, 6th Avenues were longer at 920 ft. There were only horses and wagons then and the city was still collecting water from local springs and backyard wells. Today the same grid accommodates bicycles, cars, small trucks, semi trucks, buses, subways and trains; telephone, electrical, and high speed lines; and water, steam, sewer pipes.

4th Street looking west toward 6th Ave and at one of the sharp NW turn of West 4th Street.

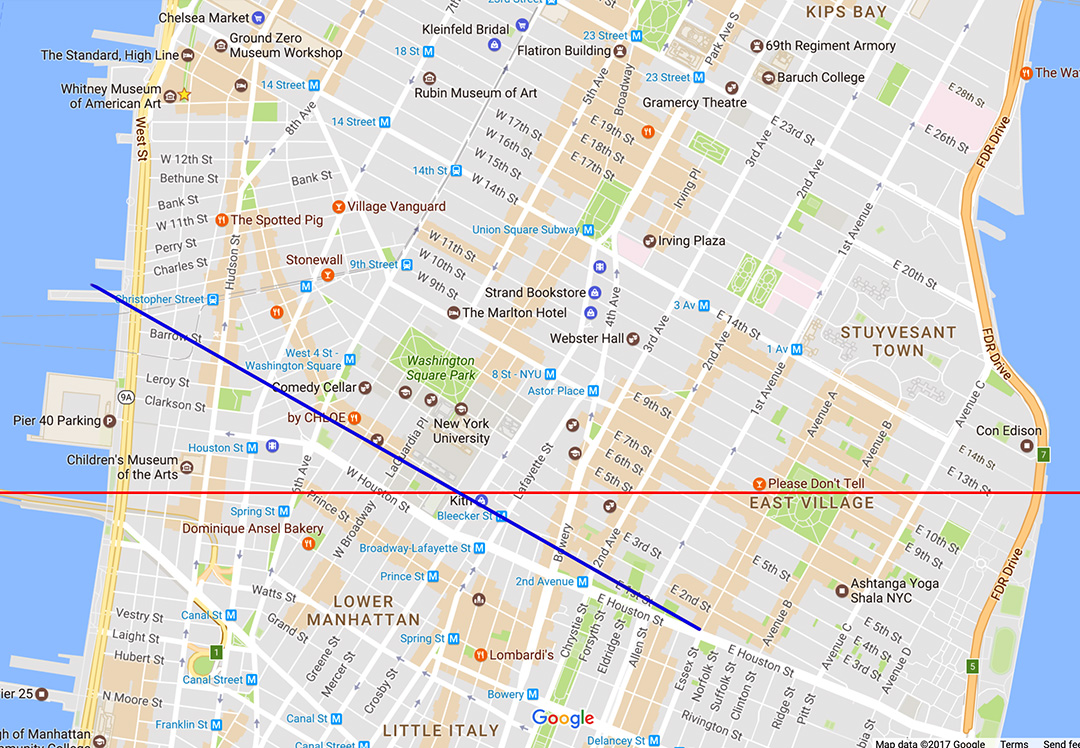

Red line is due west - East 14th street to Canal Street. Blue line is the straight line of 1st Street that goes 29 degrees northwest to Christopher St, if 1st street went to the West Village.

What is interesting for any downtown tour is how the main grid, oriented to a central axis that runs the length of the island, was carved out of "The Village". The grid's baseline is anything but a straight line. The grid starts on the east side. There is an intersection, 1st Street and 1st. Avenue – near Houston St. Then it was called North St, which wasn’t parallel with the new planned number streets. North St. was from an earlier grid laid out from selling off the old Delancey colonial estate. (The Delanceys were Loyalists and fled the city with the English.) These number streets (1 through 7) also didn’t cross the island. They stopped or actually began on the Bowery and ended east in the marshlands of the East River. Today 3rd and 4th streets do run west to 6th Avenue though on a slight NW angle and then West 4th street continues, making no less than three diagonal NW bends through "The Village" and ending at 13th street between 8th and 9th Avenues!

If you follow a straight line on today’s map from First Street to the West Village, you start from the Bowery below Bleecker Street and pass through 6th Avenue a bit south of Bleecker. You end at the Hudson River somewhere near Christopher Street. If you go due west from 14th Street and the East River you end up on Canal Street and the Holland Tunnel. What you are seeing is how tilted the island is from due North. (29 degrees East)

Looking west on Houston and 1st streets and across 1st Avenue. Named "Second Triangle" on the 1811 Plan.

Anywhere the NYC grid met an earlier grid a triangle was created and a few seemingly haphazard streets (also the reason for New York's triangle buildings). On Farm Map No. 1 the triangle that headed east to Avenue A was named Second Triangle. First Triangle was even further east where 2nd Street ran into Houston Street between Avenue C and D. Alphabet City was planned for the Lower East Side bump, the land that protrudes out towards the East River. It was much more pronounced on these old maps than it is today with all the landfill that makes up Stuyvesant Village (a large housing complex from 1 st Avenue to Ave C , 14th to 23rd Streets) and the East River Park. Avenue A and B continued up on the Upper East Side on the Plan’s grid. Today they are named York Ave and East End Avenue.

The end of the present day Bowery @5th Street. Looking up 3rd Ave and the triangle of Cooper Union and the start of 4th Ave.

Third Avenue started near 5th street coming up from the Bowery (another triangle – where Cooper Square (( really a triangle)) is today). 8th Street went further west from what today’s Astor Place and past where 5th Avenue began to Greenwich Lane (Greenwich Avenue today) which was a bit east of the start of 6th ave. Today Greenwich is west of 6th Avenue. 9th through 11th streets also ended at Greenwich which ran diagonal northwest through the start of 6th, 7th and 8th Avenues. Today West 10th and 11th streets continue but at a sharp angle directly west to the Hudson River. ( W.10th bends at 6th Avenue while W.11th bends at 7th Avenue.) On the 1811 Plan 12th and 13th Street continued through what is a 90 degree turn of Greenwich toward the Hudson River. There is a little square today called Jackson Sq. in place of that turn. 13th street picks up on the west side of 8th avenue where there is the end of West 4th Street and the beginnings of Gansevoort Street heading due west to the River. Gansevoort is the most northern of the westernly streets in the West Village grid. Once Gansevoort crosses 9th avenue, the meat packing district starts. Here you find the continuation of 12th street (parallel to the grid streets) named Little 12th street, which is not to be mistaken for West 12th street which also bends westernly and parallel with W.10th and W.11th at Greenwich.

St. Marks In the Bowery @ 2nd Ave and Stuyvesant Place looking west. The second-oldest church in Manhattan, constructed 1799. The church has been a leading East Village institution for social justice and the cultural avant-garde since the 19th century.

The farms maps show the minimal development where the grid starts downtown. In the East Village the Stuyvesants (between the two patriarchs – Nichols and Petrus IV) still held large tracts of their ancestral lands, Bowery No.1 and No.2. Some smaller tracts were laid out for relatives and relations. There was a Stuyvesant farm grid, that ran true east and west. Several roads lead off the Bowery to several Stuyvesant family manors. On the 1803 Mangin-Goerck Plan the Stuyvesant Farm Grid was planned to expand with 21 east-west streets from Houston to present day 16th street. Today there remains only one street that was part of this grid. Stuyvesant Place. It’s off 3th Ave between 8th and 9th Street running towards 10th Street. There are still three buildings standing today from before the 1811 Plan. Federal –style townhouses No. 21 (1804) and no. 44 (1795), and the Georgian style fieldstone church - St. Marks in Bowery (1799), site of the 17th century chapel of Peter Stuyvesant: making it also the oldest continuous site of Christian worship on the island. Bowery No. 3 was a smaller farm that edged east Houston Street up to the present day 4th street. Winthrop was the colonial patriarch who had already divided his land in a fanned out grid for his children, who in returned had sold individual lots. Those diagonals still shape the property lines today in the blocks from 3rd to 2nd Street to 1st Avenues between 1st and 2nd Street. You can see buildings on those blocks that are not square.

Mural by Hektad @ 2nd Ave between 1st Street and Houston, where the buildings and property lines aren't square.

The Randals farm maps didn’t cover the area of the Village below the baseline. On the 1811 Grid we see several street grids that were already laid out. Seemingly some development, definitely the sale of property and subdividing of blocks was happening. There are a few Federal style townhouses that still stand from that time. I count 4 grids on the 1811 Commission Plan for the Village not including the main 1811 Plan. 1) The Trinity Church Farm Grid is perpendicular to the Hudson River. The colonial Church of England, Trinity Church owned large tracts of West Side land from downtown to the Village. The dry sections were leased as farms. 2) The Bayard - West Grid is west of Bowery, but more perpendicular to Broadway (a street which was developed after the American Revolution) and south of Art Street which is where Washington Sq. would appear after the Plan in 1823. The Bayard's (related to the Stuyvesants) were another family of colonial landowners. 3) The Warren Grid from Christopher to Gansevoort. Infamous Admiral Sir Peter Warren and Lady Warren had built an estate there in 1741 and this land was divided among their children by the time of the Revolution.

Greenwich Village on the Commission Plan of 1811. Overlay in blue for the various grids and red for the approx present day streets.

4) The Minetta Creek Grid. This is a name I came up with. It is hardly a grid but various connecting streets and property lines in the middle of these other grids. It’s west of a waterway today referred to as a creek but stories have it rushing and flooding with an abundance of fish. The Lenape called it Manette or Devil's Water. It contributed to several wetlands in the Village, one being the area of present day Washington Sq. Freed African slaves were given land deeds near this Creek in the 17th century as they cleared the Dutch's "Bossen Bouwerie" (Farm in the Woods). The area in the 19th century was called the Negro Causeway and it is said their descendants continued to live the Village into the 20th century. On the 1811 Plan there are two parallel streets, Bedford and Herring (Bleecker), that crossed Minetta Creek from the Bayard-West Grid and headed northwest toward Christopher Street. Thus started the Warren Grid. A few streets connected the two with familiar names, like Downing and Commerce, but they were awkwardly disconnected with Hudson and Varick streets to the southwest on the Trinity Church Grid. A few cul-de-sacs like Jones and Cornelia headed north east off Herring ( Bleecker) towards a large blank area. West 4th street was not on the 1811 map. Neither was 6th nor 7th Avenue south of Greenwich Ave. They would not extend south (more than a couple of blocks) toward Lower Manhattan till the 20th century with the building of the subways. This area today has some of the quaintest single streets in "The Village" ... Downing, Commerce, Leroy, Cornelia, Gay, and Minetta Lane. It was part geography, part urbanization, part politics, and part history that defined the layout of the NYC grid in "The Village”.

To see how these farm grids developed from colonial estates only a generation before, it is rewarding to refer to an earlier map, the 1776 Ratzer map. This map was the most detailed and scaled map of southern Manhattan up to its surveyed date (1767) by a English officer with the same name.

What stands out today is how the Bowery was so central to the island. It created an arc and not a straight line, from downtown to the Village. Broadway, the straight line from Lower Manhattan would not be created till the beginning of the 19th century. The large wetlands overflowing from Collect Pond (north of City Hall and where colonial New York got their fresh water) first had to be bridged and then ultimately drained with the construction of a canal and filled (Canal Street) for Broadway and the Baynard-West Grid to be fully developed.

"The Village",east and west, on the 1776 colonial Razter Map. My overlay in pink and bold type of the present day streets and squares.

On this colonial map there is also a Road to Greenwich, coming up the west, parallel to the Hudson River, to what is today the West Village. This road, another Indian path, was seasonal at best and a planned development for the next generation since it had to cross both the massive marshes from Collect Pond and then another crossing where Minetta Creek reached the Hudson. These wetlands and waterways kept Greenwich Village and Soho isolated and truly accessible only from the main road, the Bowery. There was a road west of the Bowery off present day Astor Place, called Art Street just south of present day 8th Street that hooked up with Monument Lane. At the end of the lane there was a monument to the fallen English General Wolfe of the French and Indian War. There the road turned due west to the Hudson River. We are talking about present day Greenwich Avenue and Gansevoort Street. These colonial roads were also Native American footpaths that lead from the Wickquasgeck Trail to Sapokanikan – the tobacco fields near the Hudson River.

Meat Packing District. Looking 29 degrees northwest down Little 12th Street. The street off to the left is due west and is Gansevoort (new Whitney Museum and the start of High Line in background). The Hudson River is another block away.